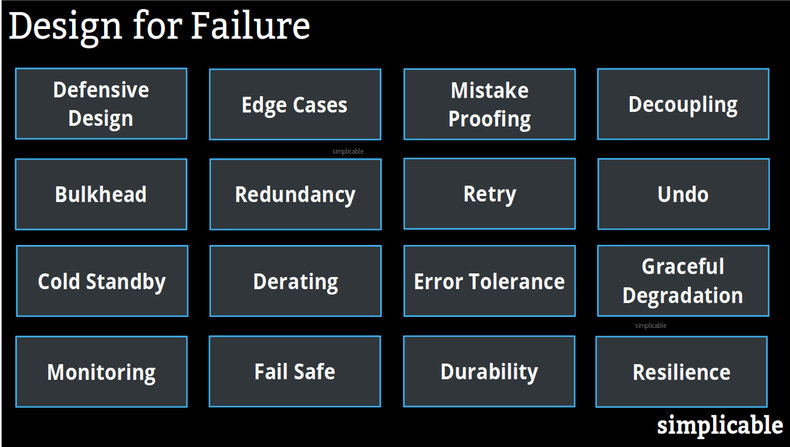

Defensive Design

The basic assumption that everything that can go wrong will go wrong. For example, the assumption that customers will put in a camera battery upside down and backwards.Edge Cases

Considering the full range of possibilities. For example, an aircraft design that considers extremely rare weather conditions.Mistake Proofing

The practice of anticipating human error and making it impossible through design such as a camera battery that is impossible to put in the wrong way due to its shape.Decoupling

Structuring designs with independent components that are decoupled such as an aircraft with two engines with completely redundant systems in areas such as control and fuel supply.Bulkhead

A bulkhead is a structure that isolates damage to one area such as a fireproof wall designed to prevent a fire from spreading quickly through a building.Redundancy

Redundancy such as a software platform that runs on 1,200 servers in 60 data centers as opposed to two servers in one data center.Retry

Retrying things that fail such as an email server that will try to resend a message that fails for several days.Undo

The ability to go backwards to correct failures and mistakes.Cold Standby

Designing things to have backups that are started up when they are needed such as a data center with two backup generators that can each generate enough power for the entire facility.Derating

Derating is a design that alters its services when something is wrong to prevent things from getting worse. For example, a vehicle that automatically limits speed when its engine is overheating or experiencing mechanical problems. This may allow the occupants of the vehicle to get to a safe place before the engine completely fails.Error Tolerance

The ability to continue operating when errors occur. Generally speaking, older software was often designed to halt at the first sign of an error. Engineers feared that continuing after an error might produce unpredictable results. Modern engineers have no such fear and tend to handle exceptions without halting execution.Graceful Degradation

Turning things off gradually as things fail as opposed to taking everything down. For example, a data storage device that can automatically stop using failed memory locations while continuing to operate with those that still work.Monitoring

Monitoring failure to implement fixes, workarounds and graceful degradation. For example, an aircraft that shutsdown an engine after a bird strike to prevent it from catching fire or damaging the rest of the aircraft.Fail Safe

Designing things to fail into a safe state such as an elevator that requires electricity to keep brakes off. If electricity fails, brakes come on automatically.Durability

Designs that are fundamentally durable such that a wide range of stresses aren't likely to cause damage. For example, a bicycle tire rim made with metal that can withstand forces far beyond anything typically experienced by a bicycle without bending or buckling.Resilience

Eloquent designs that are resilient to stress by virtue of their simplicity. For example, a city with more green space is more resilient to flooding as opposed to a concrete laden city where water can't be absorbed by the soil.| Overview: Design For Failure | ||

Type | ||

Definition | The practice of designing things to retain their quality in the face of failures and stresses. | |

Related Concepts | ||